Why

A Day Out With College Football

“Everything in Between” is about the systems, institutions, and practices that people build, “things” of a sort that sit in between us, between groups of us, between “us” and “them,” and between us and other systems and institutions that seem terribly far away: “the market,” “the state,” the universe, and so on.

In addition to my posts here, I co-host a podcast titled “Your Leadership Podcast,” which is available on Spotify and wherever fine podcasts are available. I write about law and legal education at TaxProf Blog and for several years co-hosted a podcast about technology and law titled “Your Future Law Podcast.“ My older blog about Pittsburgh and renewing cities, Pittsblog, is still available online, as is my original blog about law, technology, and governance.

The sun rose in Youngstown, Ohio last Saturday, but the temperature mostly did not. It was an unseasonably cold day – good football weather, perhaps, but not good for much else. The Bulldogs of Yale University were in town to play the Youngstown State University Penguins, and I, a smattering of other Yale alumni, Yale football alumni, Yale football parents, and Handsome Dan (the dog!) were there to witness the event.

First, to the football: This was a first-round playoff game in the NCAA FCS (Football Championship Subdivision, formerly Division I-AA), and the first NCAA football playoff game ever played by Yale. In fact, it was the first for any Ivy League champion (Yale was this year’s co-champion, with Harvard, but Yale got an automatic playoff bid by beating Harvard in the final league game). This year, the conference changed its rules to permit its members to accept invitations to play in the NCAA football playoffs. Youngstown State, an FBS/I-AA powerhouse with multiple national championships to its name, lined up as Yale’s opponent.

I’ve been to my share of exciting college football games and thrilling sporting events generally. I was in the stands for the USA v Brazil World Cup elimination match on July 4, 1994, a match that ended poorly for the USA and especially for Tab Ramos but that has to rank high on anyone’s list of exceptional sporting spectacles. I watched Stanford win two Rose Bowls in a row, the second one (1972) featuring a last-minute field goal that lifted Stanford over Michigan.

This was something else again. The Miracle on the Mahoning, one friend of mine called it later. (The Mahoning River runs through Youngstown.) Yale started slowly, the victim of some sloppy play of its own and an extraordinary first-half performance by Brungard, the Youngstown State quarterback. At the half, Youngstown State led 35-7, and more than a few Yale fans thought hard about finding a comfortable, warm indoor space to soothe frigid fingers, toes, and noses.

But I stayed. Everyone stayed. There weren’t a lot of us – perhaps 200 Yale supporters in total? (and perhaps 2,500 Youngstown State fans and students, largely the marching band, mostly on the other side of the stadium). In the cold, and feeling hopeless, we stayed. (The parents! The Yale football parents were incredible in their passion and faith!) And something amazing happened: Yale stiffened. The defense found a new resolve. The offense got crisper. Reno, Pitsenberger, Santiago. YSU scored again: 42 points. Yale scored twice: 42-20. And then in what seemed a futile gesture to many, Yale opted for a 2-point conversion and scored. 42-22. Ah well, we thought. Why not dream big?

Yale kept coming. Youngstown State seemed deflated. Another score, and another, and then Pitsenberger broke out a 56-yard run with a little less than 3 minutes to go to put Yale ahead. Ahead! And the game ended there.

What a scene in the bleachers, as well as on the field. What a glorious muffled sound your gloves make when you high-five the gloves of the person standing next to you, the person you know only as another soul braving the elements in a blue jacket or hat.

After the game ended, the Yale players gathered on the field, helmets held aloft, and they sang the Yale fight song (“Bulldog! Bulldog! Bow wow wow!”) for themselves and for everyone who stayed in support.

This Substack isn’t about sports, though. Not only about sports, anyway.

So second, about the institutional dimensions of the game:

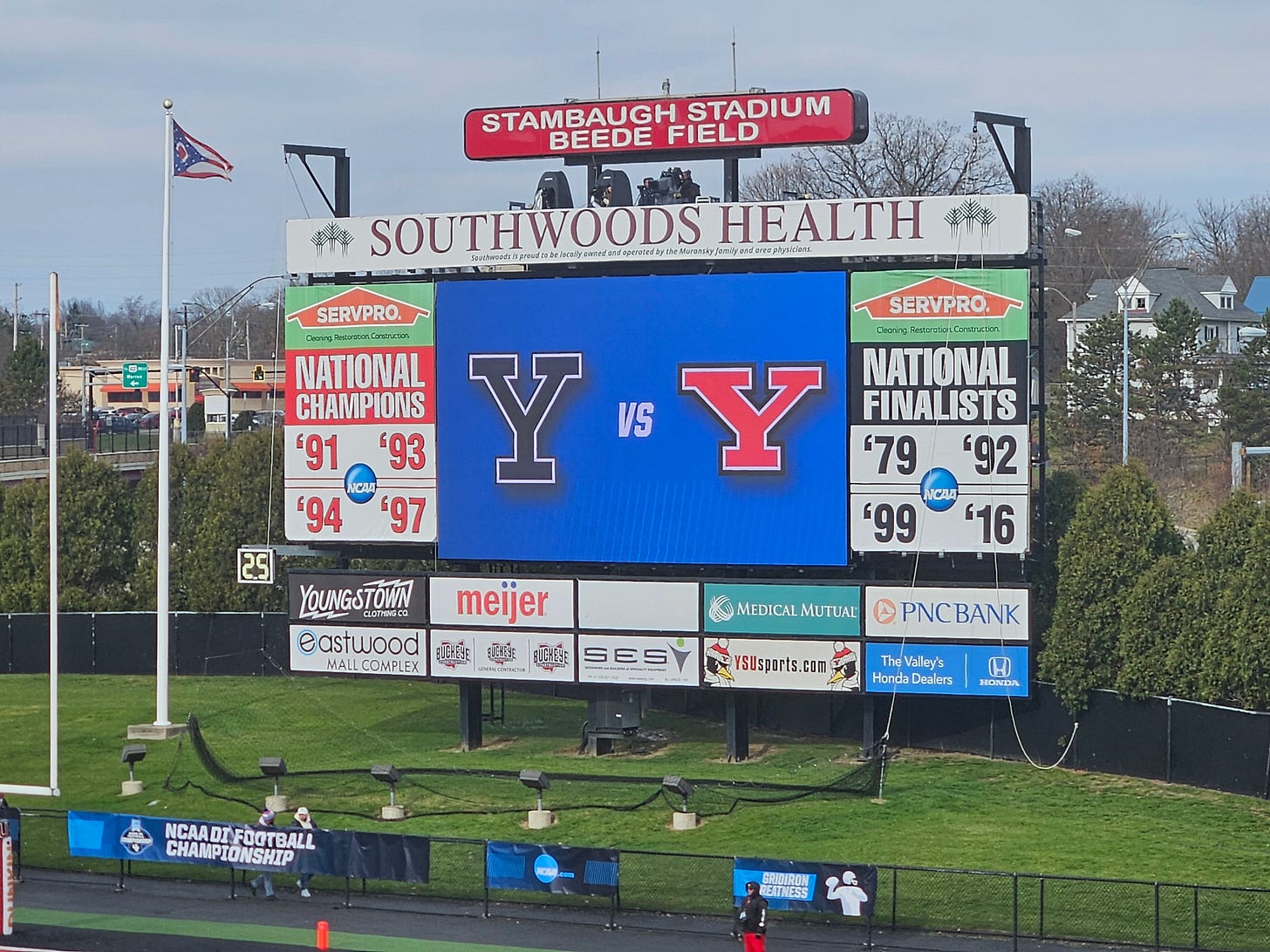

This was “Y v. Y,” literally. Today’s header is a photo of the scoreboard before the game. YSU fans sitting near me told us that the local media had played up that angle considerably during the week leading up to the game.

It may be difficult to imagine any setting other than athletics in which these two universities inhabit the same cultural sphere. Youngstown State University traces its origins to a law course in Youngstown founded by the local YMCA in 1908. What evolved into “Youngstown College” was rechartered as a university in 1955 and became “Youngstown State University,” a public institution, in 1967. Today, YSU is part of the University System of Ohio, the state’s comprehensive framework for all of its public institutions of higher education, including 14 research universities. Youngstown State enrolls roughly 12,000 students, a large majority of whom are undergraduates. The university estimates the total cost of a full year of attendance at a little less than $25,000. Youngstown State offers five doctoral degrees, in educational leadership, nursing, health science, materials science and engineering, and physical therapy. It is supported by an endowment of over $321 million.

Yale is, well, Yale: an elite global university, more than 300 years old, with an endowment of more than $44 billion. Yale enrolls more than 15,000 students, a majority of them in its graduate and professional programs.

Yale supports 35 varsity sports. Youngstown State supports 21.

And yet the similarities are as significant as the differences.

Yale and Youngstown State are both universities. They are both in the “business” of teaching and learning and research; they both employ expert teachers, researchers, librarians, and archivists. They both educate undergraduates and graduate students; they both produce research and train experts. Yale and Youngstown State each have long and distinguished histories in their communities and regions; over time, each one has taken on larger and larger roles as regional economic anchors.

Regional history matters, too, even if few of today’s students and likely not many of today’s faculty or even alumni focus on its details. Youngstown, Ohio is an older former steelmaking center, roughly halfway between Cleveland and Pittsburgh, that has struggled mightily since the end of steel in the early 1980s. Read George Packer’s book “The Unwinding” to learn more about Youngstown’s late 20th century history. New Haven, too, was simultaneously a “mid-point” city (between New York and Boston rather than between Cleveland and Pittsburgh) and an industrial power in its own right. New Haven’s industrial era largely ended in the late 1970s, more or less concurrently with the closure of Youngstown Sheet and Tube. New Haven’s 20th century struggles are chronicled in Doug Rae’s “City: Urbanism and Its End,” among other places.

New Haven’s industrial history is mostly hidden from contemporary view. Youngstown’s history is omnipresent. In the stadium, great Youngstown State plays and key moments were marked by the scream of a steam whistle mounted at one end of the stadium, a tribute to the area’s steel history.

While I enjoy the pageantry of college sports at all levels, even on a wintry day with only a handful of fans in the stands, like a lot of people, including a lot of people who work in universities, I’m skeptical of the amount of time and money that goes into operating and celebrating Big College Sports (my own “BCS”). For all of the many flaws of the college sports system, or system of systems – for all of the ways in which college sports exploits the athletes, distorts budgets, and corrupts public understandings of why, exactly, colleges and universities exist – there is something remarkable and levelling about the spectacle surrounding the events and about actual play of the games.

In Youngstown last Saturday, to person I am sure that everyone in the stands and on the field was aware of the status and economic differences between the two universities. I spent most of the second half standing (to keep warmer) and chatting with someone who identified himself as a Youngstown State faculty member. Neither of us said anything to the other about what divided us as well as what linked us. We both knew. What we shared aloud was our wonder at what was unfolding in front of us. Me: elated. He: discouraged.

There is no rivalry between Youngstown State and Yale, not in any meaningful sense, but in a broad sense, there is both conflict and complement. Conflict: Yale and its peers draw down resources that in some senses might be better directed to broad, mass higher education. Complement: Yale and its peers also produce research and scholarship that institutions of mass higher education are simply not designed to produce.

But when the referees’ whistles blew, none of that mattered. Social scientists might call this “polycentricity on the ground.” Football fans know it simply as a set of arcane, even bizarre rules and rituals that they do not need to understand in order to love and share.

I accepted a long time ago that my own university, in Pittsburgh, plays a role in the culture of Western Pennsylvania that is disproportionate to its economic and educational contributions, largely by virtue of the presence (and successes, and sometimes failures) of its athletic teams. Pitt even plays Youngstown State in football from time to time. Pitt usually wins. But not always. I borrow again from Erich Segal’s “Love Story”: polycentricity means never having to say you’re sorry.

After the game ended, my path back to my car took me past a large group of YSU supporters who were obviously standing outside of the stadium gate, expecting the players to exit after showering, changing, and talking with each other and their coaches. No one spoke to me; faces were polite – understanding – a little grim. The mood was somber but resolute. One might plausibly connect the fortitude of Penguins’ supporters to the fortitude of Youngstown full stop. Yale football moves on to its next playoff game, at Montana State University, in Bozeman. As I got in my car, the YSU fan getting his car next to mine said to me, soberly but in a spirit of what may have been solidarity: good luck next week.

You can be sure that Youngstown State football will be back next season.

What others have to say

Selections from new-ish commentary about the institutions of higher education and institutions of expertise, shared because these folks have me thinking, not necessarily because I agree.

When I am not thinking about the institutional dimensions of higher education, I try to keep track of the institutional dimensions of AI. Here is Azeem Azhar, at “Exponential View”:

In early 2025, sovereign AI was mostly posture. The AI landscape has become starkly bipolar: the US controls 75% of global AI compute, China 15%, leaving everyone else marginalised. You can adopt US/Chinese AI systems and become vulnerable to data exploitation, service restrictions, embedded values, and unfavourable terms. Or accept weakness, limit adoption and fall behind as frontier states achieve economic, scientific, and military breakthroughs.

You can see the logic hardening. Britain is building national infrastructure with Nvidia; the Gulf is spinning up its own polity via the $100 billion MGX vehicle. OpenAI’s “Stargate” initiative fits this fractured landscape perfectly. Stargate UAE offers a gigawatt-scale compute cluster under US-aligned governance. Meanwhile, South Korea joins the orbit as a chip arsenal, and Saudi Arabia finances “AI factories” for local workloads.

Even Brussels is softening regulations to keep champions like Mistral onshore. Officials now discuss compute and models as strategic assets to be rationed through alliances, not left to the market.

The challenges are most acute for mid-sized and smaller nations, where mid-sized means anything smaller than the US or China. One possible route may be multinational or minilateral approaches that involve pooling capabilities or resources, as argued in this working paper from an Oxford University research group. This question is also the focus of a working group I co-chair on how governments need to approach next-generation computing infrastructure.

This logic virtually guarantees a splintered world. We are moving toward distinct US-aligned, China-aligned, and “non-aligned” stacks. The era of the borderless internet has come to an end; the era of the sovereign stack has begun.

My bookshelf

Like a lot of academics, I read a lot. Like a lot of law professors, I read a lot about law and about governance. But I also read a lot of things just for fun and a lot of other things because you never know where interesting ideas might come from.

Completed: Helen Garner, “The Season” (Penguin Random House, 2024).

From the publisher’s site:

Helen Garner is one of the most “prodigiously gifted” writers of our time (The New York Times Book Review), best known for her intricate portraits of “ordinary people in difficult times” (New York Times). In The Season, she trains her keen, journalistic eye on the most difficult time of all: adolescence.

Garner and her grandson Amby are deep in the throes of a shared obsession with Australian football—or “footy”—as Amby advances into his local club’s Under-16s. From her trademark remove, Garner documents the camaraderie and the competition on the field: the bracing nights of training, the endurance of pain, the growth of a gaggle of laughing boys into a formidable, focused team.

The Season is part dispatch on boyhood, chronicling the tenderness between young men that so often scurries away under too bright a spotlight, and part love letter to parenthood and family, as Garner becomes enmeshed in the community that gathers to watch their boys do battle. The Season finds Garner rejoicing in the later years of her life, surprised to discover their riches—a bright, generously funny, exuberant book from one of our great living writers.

Roger Bennett (Men in Blazers) is mostly right when he writes: “A book that explores the themes of adolescence, masculinity, the transcendence of sports and the experience of connection through fandom. One of the most humanly enriching books I have read this year.” I have not encountered Helen Garner before, let alone read one of her books. There will be more of that. But the football here is only incidental, even if it is central. “[A] kind of poetry, an ancient common language between strangers, a set of shared hopes and rules and images,” she calls it. This is a finely observed account of a dance between youth (life being lived, and life to come) and mortality (life as it ends, as it must). Garner sees both with extraordinary clarity, even if what she records is mostly an account of trainings and games and her conversations with her grandson.

Next on my list, when I can get my hands on the library’s copy: Ann Packer, “Some Bright Nowhere” (Harper Collins, 2025). Yes, this is an “Oprah’s Book Club” pick, but that’s unimportant to me. I have a quirky historical connection to the Packer family, amazing writers, all of them. I have read just about all of the work of her brother, George. Now on to Ann.

Thanks for sticking with me.

I love the description of the game. What a win!!