“Everything in Between” is about the systems, institutions, and practices that people build, “things” of a sort that sit in between us, between groups of us, between “us” and “them,” and between us and other systems and institutions that seem terribly far away: “the market,” “the state,” the universe, and so on. Once a week, usually on a Monday, I’ll have something new.

What about law? As I’ve tiptoed into the newsletter waters, I’ve deliberately steered around the institutions that I know best, professionally speaking: all things “law,” beginning but hardly ending with law schools, particularly U.S. law schools. Today, I take a hard turn and dive in. Or dive back in. I’ve been writing and talking the past, present, and future of law schools for close to 20 years, which is almost as long as I’ve been a full-time law professor. Most recently, for about four years, from 2019 through the end of 2022, with Dan Hunter (now Dean of the law school at King’s College London), I co-hosted a podcast about the future of law called, memorably, “The Future Law Podcast.” Some of my thinking is motivated by my origins as an IP and law-and-technology teacher/scholar, some is motivated by my present identity as a knowledge commons/governance teacher/scholar, and some is motivated by my having learned quite a lot along the way about higher education finance. Some is motivated by … other things, which I’ll introduce here and there as I go along.

I’ve written out a long-ish summary of my answers to “what about law?,” and law schools in particular, and in this edition of “Everything in Between” and in editions to come, I’ll dole it out, bit by bit. Substack and all of you readers don’t take kindly to 7,500 word essays.

So I’ll start with the end, and then circle back to the start.

The end, to sum things up, is that U.S. law schools are, on the whole, hurting financially. Not hurting a little bit; they are hurting a lot. If law schools were examined as stand-alone businesses (which in US higher education terms they usually are not, or should not be, for reasons I’ll get to later on), they’d be deeply under water.

There are obvious exceptions to that judgment: elite private law schools that are parts of elite private universities, which charge premium rates to students and which are backed by massive endowments; and a handful of non-elite law schools, both public and private, that have by circumstance or plan figured out how to more than cover their costs. Some additional number of law schools have managed to secure stable relationships with their “mother ships” and are being supported, comfortably, by stable wealth transfers inside the university. But I’ve talked to lots of present deans and former deans and others over the last couple of years, and none has challenged my core conclusion.

I’ll get to the reasons as I go along, and I’ll get to whether anything ought to be done about this, and if so, what, but before returning to the beginning I’ll offer two related observations. Call these provisional answers to the usual question, “so what?”

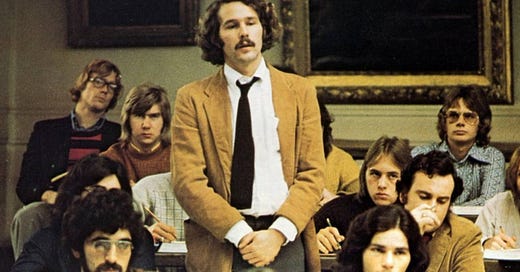

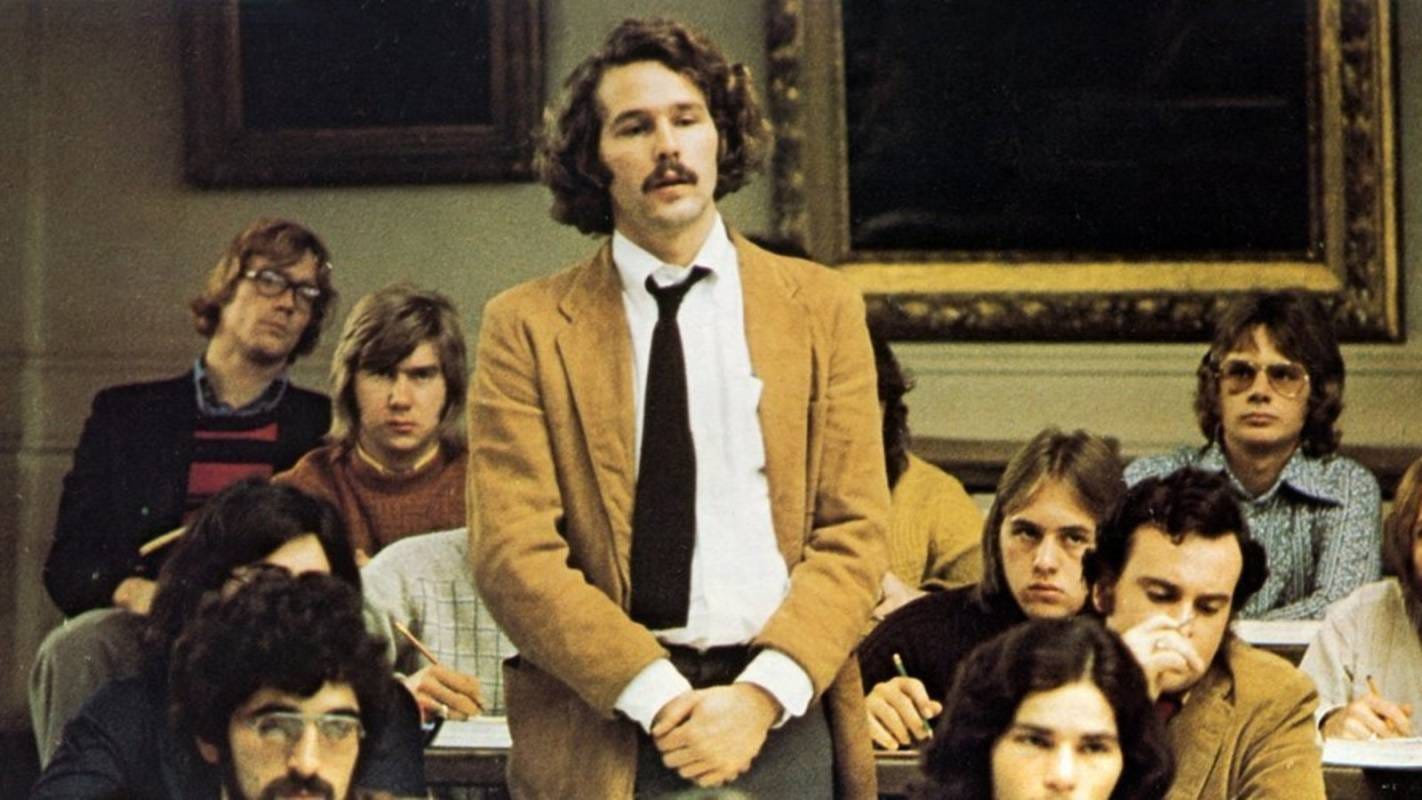

One is this: as much as I talk to academic leaders, I also talk to colleagues, “ordinary” faculty at law schools in the US, and I talk to practicing lawyers and to judges. And on the whole, this comes as news to them. Startling news, in fact. To the outside world, focused as it often rightly is on maintaining the integrity of legal systems and the rule of law, U.S. legal education offers a kind of first line of defense. And from outside the walls of the academy yet within the confines of the legal profession, everything about law schools seems to be just fine. Students apply, enroll, graduate, and take their places in the system in large numbers, following, one might imagine, the game plan that Mr. Hart (above, in The Paper Chase) hoped to follow when he enrolled at Harvard Law School. Sure, law school should be cheaper for students; sure, graduating students are often burdened with crippling debt; and sure, airy theoretical law school courses should be abandoned in favor of hard core, practical, be-a-fully-equipped-lawyer-on-day-1 training. But versions of those criticisms have been around for decades. Evolution has always been welcome, though usually far from successful, let alone complete; law schools, like universities, think of themselves as productively adaptable institutions.

Not so fast.

Two is this: U.S. legal education isn’t some strange barnacle on U.S. higher education generally, running up costs and relying on teaching methods and scholarly habits that are dragging down otherwise healthy systems of post-secondary education. No, their parent universities are in heaps of trouble themselves - financially, culturally, socially, organizationally, epistemologically, and in just about every other way one might imagine. Few of those challenges have to do only with Generative AI, or with political shenanigans in state legislatures over the last 20 years, or with whatever one thinks is right or wrong about teachers in the classroom today or about students protesting around the campus. Universities at all levels, from the elites down to community colleges, face systematic, structural problems that have been decades in the making. Law school problems are distinct in some ways but microcosmic in others, and structural in equal parts.

That’s where this is all headed, eventually. Big picture stuff. But I’ll start small, or relatively small at least. If you’d like to get ahead on the reading, what follows next and in weeks to come borrows from this long piece. I hope to hear reflections and reactions to all of it.

I attempt to demystify the opaque financial and cultural systems that drive US law schools today. I takes as a given that many (but not all) law schools are under enormous financial pressures, for reasons that relate to financial pressures on the legal profession as a whole (external factors, in other words) but that also relate to the evolution of structures of higher education and legal education through history (internal factors). Among practicing lawyers and even many law professors, law schools are, proverbially, rolling in dough. For reasons that will be explained below, that isn’t true. Law schools are awash in red ink. The questions are why, and what might be done about that?

Who need answers to those questions? Who might care? The answer is: anyone who wants to stabilize and animate a sustainable sector of “US legal education” going forward. I don’t write “law schools”; the phrase “law schools” is useful for historical reference but may turn out to be too limiting looking ahead. The future of legal education, and by extension the future of “lawyers” and “law” itself, depend in significant respects on understanding and addressing the economic infrastructures of its key institutions – education, practice, planning, dispute and conflict resolution.

To many present and former law deans and other legal leaders, much of what follows is likely to be uninteresting, simply because this is the world that they have been living in. It may be – should be – illuminating to many law professors, who are often understandably comfortable ignoring the marketplace logic of their places of employment. It may be – should be – illuminating to provosts and other senior academic leaders whose domains include law but also cover larger, and sometimes very large, universities. And it should be informative for present and future law school donors, law school alumni, philanthropists, and members of the profession generally.

Stay tuned. There is more to come, next week.

Thank you for handing us “this dime … to call [our] mother …” (The Paper Chase). You look good in yellow!