“Everything in Between” is about the systems, institutions, and practices that people build, “things” of a sort that sit in between us, between groups of us, between “us” and “them,” and between us and other systems and institutions that seem terribly far away: “the market,” “the state,” the universe, and so on. Once a week, usually on a Monday, I’ll have something new.

Alice Brock passed away the other day. She was the “Alice” of Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant,” where “you can get anything you want.” Except Alice, of course.

Last week I wrote about the origin story of the contemporary university. It is often said that the university is a medieval institution, undoubtedly because the original and most famous Western universities were established in the 11th century (Bologna) and the 12th century (Paris), largely to train men for the clergy and the civil service.

In my telling, today’s universities and colleges are the evolved products of the late Industrial Revolution. The dual functions of “higher” education - truth, and labor - remained the twin pillars of institutional design - but in the hands of turn-of-the-century funders and leaders they were domesticated and diversified. Thanks to the stewards of the Enlightenment, “knowledge” was no longer a static “thing” - “truth” - to be conserved and passed down; universities were to be fonts of new knowledge. And labor was not merely the technical expertise needed to administer the gears of the hierarchical state; labor was above all managerial, needed for everything from Chandler’s “Visible Hand” to the farms staffed by the products of the original land grant universities.

In short, the medieval university became the Industrial University (initial caps for emphasis) because the key social problems and opportunities faced by late 19th century society writ large were orders of magnitude greater and more complex than the social problems faced before.

How to break down and address those problems, institutionally speaking? Metaphorically, in the way that factory owners figured out how to reap the benefits of division of labor. Specialization. To borrow a concept from Herbert Simon’s “The Architecture of Complexity,” “near decomposability.” Complex systems understood in terms of subsystems.

So out went the seven original liberal arts, the foundation of the mandatory college curriculum. In came the elective system, pioneered at Harvard. Urbanization, factories, and market finance came to West, along with electrification, indoor plumbing, the telephone, and the automobile, and their associated economic, political, and cultural challenges. More or less at the same time, the marketplace came to the university. Out with uniformity, in with every man choosing his own path. The university’s systems and structures offered conceptual and bureaucratic infrastructure, adding departments and schools and institutes to lock in that premise. Faculties and disciplines built up intellectual and budgetary inertia.

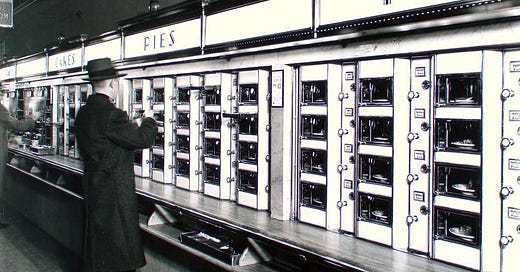

The result? In simplistic terms, indulge me this metaphorical leap: “you can get anything you want” at the modern university. My “Automat” image captures its culinary character in practice: knowledge is packaged and delivered in easily recognizable and quickly digestible forms. Yum.

Of course, there are restaurants and then there are restaurants, as Paul Freedman’s “Ten Restaurants That Changed America” reminds us. Some universities set the pace; others extended our intellectual palate; still others were and are notable for their relatively low cost and ease of access.

But the key social problems and opportunities faced by late 19th century society writ large are not the key social problems and opportunities faced by early 21st century writ large. The late 19th century witnessed the invention of the systems of market capitalism that were expanded and refined during the 20th century. That inventive era is largely behind us. The 21st century is confronting both the legacy of that expansion (the costs of combustion; North/South health and wealth gaps) and the enormous scale of its redirection. We already know that the 21st century is being defined economically, culturally, and politically by the virtues and drawbacks of systems that produce intangible things (ideas, data) rather than by the virtues and drawbacks of producing tangible “stuff,” and by conflicts between local and global visions of the good, among other things.

At Anecdotal Value, Hollis Robbins describes two distinct conservative approaches to higher education reform that she discerns in the current political climate. One is the “Efficient Workforce Development” camp; the other is the “Classical Liberation Education/Western Civilization” camp. I’ll accept her description but point out the obvious, in a way agreeing with her conclusion: these are both “Back to the Future” perspectives, in different ways trying to recapture and re-institutionalize a version of higher education that I am coming to think of as simply out of date, despite their currency in the moment. She points to this recent White Paper, coming out a Stanford convening, as a starting point for a new path forward, a new “academic social contract.” (A marker: I will have something to say about that, down the road.)

I’m not one to jump on board a contractarian framing, but I do share the instinct that universities are in many ways “about” knowledge (figuring out what it is, producing it, storing it, studying it, sharing it), and in other ways are “about” people (“producing” them, in a way or ways), in ways that reflect as well as drive large-scale social change. Universities as institutions, and institutions within universities, are more or less “knowledge” systems and subsystems or “people” systems and subsystems, or both. That’s been true, in a general sense, for more than a thousand years. Sources of massive current controversy and debate in higher education - adjunctification, EdTech, student debt, the trustworthiness of scientific expertise, among other things - are, in my view, symptoms rather than causes of social changes outside the university that are putting pressure on legacy knowledge/people blends and their institutional payoffs. The Industrial University model blended knowledge and people in specific but contingent ways. Each college or university operating on the Industrial University model - which is to say, almost all colleges and universities, including many outside the U.S. - blended them locally with different emphases.

Are “knowledge” and “people” still the right core ingredients for higher education’s institutional design (sorry; the gastronomic metaphor is difficult to escape)? If not, what should be in the mix? If so, in what proportion(s)? And who is to say?

There is much more still to come.