A University Bundle of Joy

A heuristic to start the new year

“Everything in Between” is about the systems, institutions, and practices that people build, “things” of a sort that sit in between us, between groups of us, between “us” and “them,” and between us and other systems and institutions that seem terribly far away: “the market,” “the state,” the universe, and so on. Once a week, usually on a Monday, I’ll have something new.

Thinking and writing about the future of the university almost inevitably falls into the nitty-gritty of thinking and writing about the past of the university. Some of the thinking and writing is anchored in the ground-level question “how on earth did we get here?”; some of it is asks the comparatively untethered question “how do we get back to the Edenic ideal that existed, somewhere and when long ago?” Today, I want to start to offer mid-level aids to navigation. All of what follows is preliminary and tentative. For now I’m sharing some patterns in formation in my own thinking and hoping to sharpen them along the way.

I have three intersecting “maps” at hand, heuristics that may help observers and practitioners stake out where they (we) are and where they (we) might want to go. Like almost all mapmakers, I’m drawing on a lot of sources, and I haven’t yet figured out precisely how to integrate them.

To start with, I’ll distinguish between the “stuff” that universities do; the processes that universities undertake – both processes as to what and who comes in the proverbial door; processes as to what and who exit at the proverbial other end; and processes as to who and what stay behind; and the decision-making systems that govern both “stuff” and institutional processes.-

Today, it’s about the “stuff,” which is to say “what does the university ‘do,’ programmatically?” Later on I’ll talk more directly about processes and about decision making.

The “stuff” map has, I think, two axes.

Axis one:

Capitalism versus commons.

“Capitalism” is my catch-all label for the critique that contemporary colleges and universities are too little in thrall to ideals of the modern market economy, now accelerating at light speed via generous doses of the processes and products of Generative AI. The critique goes more or less like this: College graduates today are insufficiently prepared to apply useful skills to stability-securing careers. Underwater basketweaving and its cousins – nearly all of the humanities and the qualitative social sciences – ought to be reduced in scale and scope or banished from the curriculum altogether, and their faculties remitted to the vagaries of various marketplaces. (That is, those professors should learn to work for a living.) This classroom version of “more markets, please!” is realized in actual experience as the university-as-administrative-system, with courseware sneaking into every nook and cranny of the teaching-and-learning experience and replicable, automatable “content” delivered by inexpensive (machines) (contingent faculty) supplanting wisdom and knowledge earned in dialogue with disciplinary masters.

There are more and less severe versions of “capitalism” as a critique of higher education, and as a conceptual baseline your “capitalism” mileage may vary, as capitalism itself has done through history. Today’s critique seems to be anchored largely in consumer capitalism (with a complementary dose of surveillance capitalism); 50 years ago, the critique sounded more in 20th century market capitalism; 150 years ago, related critiques were tied more directly to industrial capitalism. These are not hard-and-fast distinctions, but they’ll do to set up the contrast with the other end of the axis, which I call “commons.”

Pause for a moment to observe that “commons” means different things to different people in different settings. My own research area is mostly “knowledge commons,” which I and my colleagues use to designate “governed sharing” of knowledge in communities, rather than “open and free” access to knowledge. Here, instead, I’m setting semantic niceties aside to connect “commons” in the university setting to concepts that are more typically part of the syntax of this (non-capitalist) end of the reform debate, such as the idea (and the ideal) of the “liberal education.” I nod here to Newman’s classic text “The Idea of the University,”, and to Pelikan’s re-reading of Newman.

The university as commons means, among other things, that the university should be a home for a liberal education, relatively free of hierarchical supervision and monitoring of either scholar or student aside from the interwoven conversations that constitute the teaching and learning relationship itself. “Commons” takes seriously the idea that the university is defined by the intersection of “knowledge” (the pursuit, generation, storage, and transmission thereof, some of which is “more and better” and some of which “preserve unchanged”) and “community” (communities of researchers, scholars, teachers – who may but need not be the same things – and students – who come in many flavors). And “commons” is often the root of the critique that “the university” has become overly commercialized, not only with respect to things like intercollegiate athletics but also with respect to technology transfer practices.

The commons formulation doesn’t discard the career aspirations of students or the inventive ambitions of the faculty – capitalism and commons are not pure antagonists, in my telling – but it orients institutional priorities and the privileges of human judgment at the level of teaching and research practices in different ways. Knowledge is an ethic rather than an instrument; the pursuit of knowledge is simultaneously a mode of individual and collective understanding (and, at times, improvement) and also a mode of craft wisdom. To learn to read, interpret, and critique a text - the heart of the contemporary humanities – is to learn to read, interpret, and critique everything, full stop.

There is much more to be said about axis one, including examples from 19th century as well from the present day. The point for now is that the “commons”-ness of the university is a long-standing model as well as ideal – but in a way no more long-standing or ideal than the “capitalist” model or idea. Within a given university and within a given (say, national) university system, changes can be discerned as one model and then the other tends to dominate. The original Bolognese university was training 12th century bureaucrats, both Catholic and secular, to a significant degree. The invention of the elective curriculum in the U.S. in the 19th century was in a way a shift from a more or less “commons” understanding of higher education to a more “capitalist” one. The development of “land grant universities” was, likewise, a huge nudge in the “capitalist” direction. That tempts me to conclude that the direction of travel along this axis operates in one way only. I think that’s not necessarily accurate, but I’ll defer the question to a later time. Instead:

Axis two:

Unbundling and bundling.

Critiques of “bundling” in the university have a long history. I return to the theme in order to broaden it. “Bundling” might refer to clusters of knowledge, sometimes called disciplines. These might refer to clusters of people, sometimes called departments, or faculties, or colleges, or schools, or centers, or institutes. These might refer to functions that cut across teaching and learning. Clark Kerr, the former chancellor of the University of California Berkeley and president of the University of California, once quipped that “the three major administrative problems on a campus are sex for the students, athletics for the alumni and parking for the faculty.” There, Kerr was (among other things) ruing the challenges of bundling. Elsewhere, he celebrated it; in his famous work, “The Uses of the University,” he largely celebrated the “multiversity,” the combination of research intensity and undergraduate, graduate, and professional education that characterized the most ambitious post-WWII U.S. universities.

Kerr’s “multiversity” itself demonstrated that bundling, whether it operates administratively or academically, is not a given feature of university life. Put differently, it’s fair both historically and prospectively to wonder whether the benefits of bundling (including some administrative efficiency; economic cross-subsidization; infrastructure leveraging; cross-disciplinary collaboration; harmonization of academic integrity and academic freedom standards and practices across field; and broader student experiences) outweigh their costs (the massive administrative bureaucracy needed to keep so many disparate balls in the proverbial air at once; more or less equalizing treatment of faculty and students across dozens if not hundreds of different disciplines – not to mention dozens of athletic teams and university/ community/ industry/ government interfaces).

Again, the point is that these are problems with deep historical roots; there is little truly novel in them. The earliest “universities” differed quite dramatically from their modern descendants in all sorts of ways, but the core of the difference lies in the fact that the university model emerged out of a medieval form of what we would call, today, collective bargaining. Students had been negotiating with tutors for one-to-one instruction. The tutors exploited their market power and information asymmetries to charge some students more than others. The students banded together and demanded standard pricing. The “faculty” collectivized as well. An institutional design grew up out of a flawed market.

(Note, of course, how quickly and easily a “capitalist” metaphor slipped in to my nickel-tour historical summary.)

In what respects might the modern university be “unbundled”? All universities and colleges today are different bundles to begin with, so perhaps the question ought to be: what are the right bundles, and what are the wrong bundles? And that begs the question – according to whom, and per what standards?

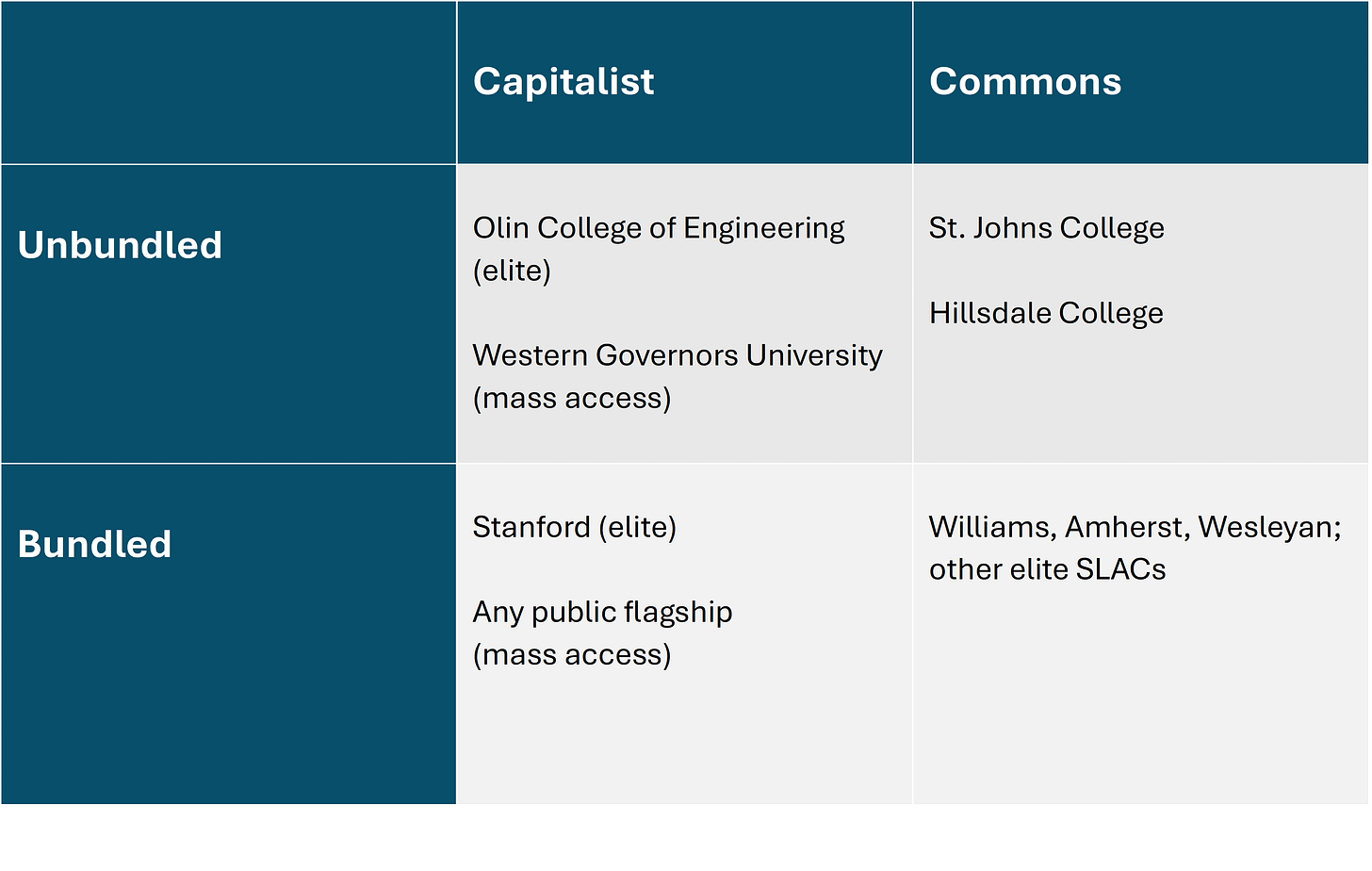

Combine axis one and axis two and we get that favorite object of academics everywhere, the 2 x 2 matrix. And any particular university or model of a university may be located somewhere within the matrix, at any given point in its history. I’ve filled in this one with a small set of preliminary cases. Where have I gotten this wrong? Where have I gotten it right? What additional or better examples might make – or undermine – my case?

Here, I’ve deployed the 2 x 2 matrix at the level of the umbrella institution. It should be obvious that the matrix may be equally useful in thinking through the design and functions of schools, colleges, departments, and programs (in academic terms) and of administrative offices (alumni relations, development) and functions (athletics; libraries and collections). Universities are fractal; the heuristic has a fractal character, too.

What’s next? I have a heuristic. What questions does it answer (or, better, help to answer)? Whose questions are they? Are they important and useful questions? How might it answer them?

I will be back.